Latin has them, Russian has them, and even English has preserved a tiny trace of them. I’m speaking of case endings, those grammatical boobytraps that make second-language speakers hesitant to finish their words. In Latin it’s rosa, rosae and the rest, in Russian it’s the thing that made me give up studying the language and in English it’s the difference between greengrocer and greengrocer’s.

Cases, however annoying, aren’t useless, but nor are they indispensable, and lots of languages do without them. So why haven’t Latin and Russian done away with them? Sorry to correct you, but Latin has: see Spanish, French and the other daughters. With Russian and most other Slavics, the answer is filial piety. Children, even teenagers, even rebellious teenagers, speak largely the way their parents taught them to.

The more interesting question really is: how did cases come about?

In general terms, endings are often former words clinging on for dear life. A clear example is the regular English past tense ending: the –ed of forms like I baked are the remains of an old Germanic word, *dedē, which has also given us did. So baked can be thought of as bake-did. (Probably, anyway. No surviving witnesses.)

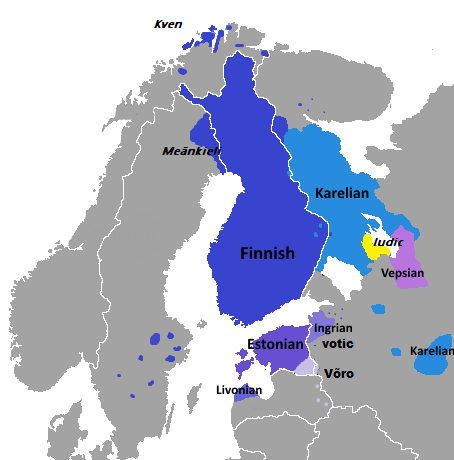

How about cases? Frankly, I don’t know about the origin of the Latin and Russian cases, nor English’s pathetic one single specimen. But I’ve just come across a beautiful example of how ome particular case came about in Karelian. You know – Karelian? Spoken in Karelia? Karelia, like the UK, is a region bordering on the EU. It’s the part of Russia that borders on Finland, is Karelia. Its language is a close relative of Finnish.

It’s like this. In the deep past, say 25 centuries ago, there was neither Finnish nor Karelian, only a language now known to linguists as Balto-Finnic. In Balto-Finnic there was a word kanssa meaning ‘people’. In modern Finnish, it still exists, but it now means ‘with’. One can see why: people are company, and ‘with’ expresses who the company consists of. (In French, an old word for ‘house’ now means ‘at’, as in ‘at my parents’ [house]’. That’s how prepositions come about.) Ah, and the Finns place their prepositions behind their nouns, that’s also important to know. They’re not so much pre- as post-positions. They don’t say ‘with the rebellious child’ but ‘the rebellious child with’. And they don’t have articles, so: ‘rebellious child with’.

Okay, so in Finnish, a noun has become a postposition. Next, there’s another offshoot of Balto-Finnic called Vepsian, spoken a short way (250 verst or so) east of Saint Petersburg. Here, the old word kanssa has been reduced to ka. Also, the postposition has changed to a suffix, meaning that it is no longer a word, but an ending. We have already seen both changes in our English example: the old word dedē got reduced to ed and became an ending, -ed: you can’t cut baked in two and shove something in between. Same with -ka in Vepsian. So if Finnish has ‘rebellious child with’, Vepsian has ‘rebellious childwith’, or perhaps I should write ‘rebellious childwi’.

And then there is, as promised, Karelian. Here, the form has become –kela – don’t ask me where the additional letters come from, I don’t know; the experts are confident that the whole thing has the same origin. As in Vepsian, this -kela is stuck at the end of the word. But something new has happened: while it still means ‘with’, it now gets attached to both the noun AND the adjective. ‘With the rebellious child’ in Karelian is something like ‘rebelliouswil childwil’ (where -wil is my silly way of rendering –kela in English). Which is very similar to what you would see in Latin or Russian. Not literally of course, but structurally: -kela is a case ending.

So there you have it: from noun to case in three simple steps. If you want to know more about these sorts of processes: I read it in Peter Trudgill’s book Millennia of Language Change. Trudgill is a lively writer, so if you’re madly into language and can handle a fair amount of linguistic jargon, I recommend it. His source, in turn, was Lynne Campbell’s article On the linguistic prehistory of Finno-Ugric. That sounds like a plodding read, but I could be wrong.

Gaston, glad to see your email once more. I just learned something of interest. It’a a trivia question: what US President, as a toddler, learned to speak a language other than English? Also, what is this language? Bear in mind that to become President, one must be born in the US. I didn’t know, but should have guessed. It’s Matin Van Buren, elected in 1836, who started speaking Dutch.

Jim Warner

LikeLike

I guessed it! But it makes me wonder: is there really just one? Probably yes. Obama must have spoken Indonesian as a young child though, as a second language. Probably no Dholuo (of the Luo people) nor Hawaiian.

LikeLike

And sometimes, a case ending becomes a word, like bus being a short form of omnibus (Latin, ‘for all’, dative ending). I often cite the rare Spanish word busilis, ‘the ‘crucial / critical point’, which shows the sae ltin edning in its first syllable. It originated as part of Latin in diebus illis (‘in those days’), the first words of the nativity account in the the gospel according to Luke (2:1-20), so one o the most influential parts of the bible. It was understood as *in die busillis (‘in the day of busilis’), with the last word interpreted as separate noun.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, bus is a well-known example, but busilis is an amazing titbit! A different sort of example where case endings end up in new nouns are the German words Wenfall (accusative), Wemfall (dative), Wesfall (genitive) and Werfall (nominative), the last one not to be confused with Werwolf (werewolf).

LikeLike

WERWOLF

Do you know the famous Werwolf poem by Christian Morgenstern, based on the declination of wer?

https://www.literaturport.de/literaturlandschaft/orte-berlinbrandenburg/text/der-werwolf/

hilarious!

LikeLiked by 1 person