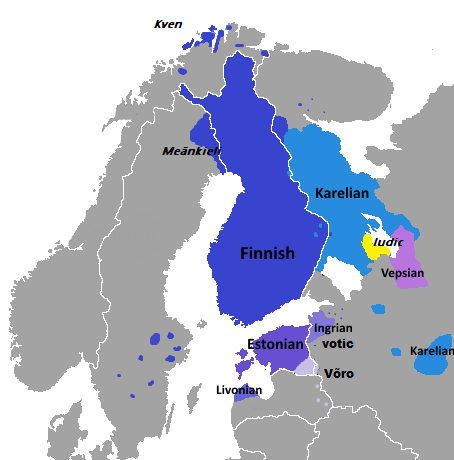

Latin has them, Russian has them, and even English has preserved a tiny trace of them. I’m speaking of case endings, those grammatical boobytraps that make second-language speakers hesitant to finish their words. In Latin it’s rosa, rosae and the rest, in Russian it’s the thing that made me give up studying the language and in English it’s the difference between greengrocer and greengrocer’s.

Cases, however annoying, aren’t useless, but nor are they indispensable, and lots of languages do without them. So why haven’t Latin and Russian done away with them? Sorry to correct you, but Latin has: see Spanish, French and the other daughters. With Russian and most other Slavics, the answer is filial piety. Children, even teenagers, even rebellious teenagers, speak largely the way their parents taught them to.

The more interesting question really is: how did cases come about?

Continue reading

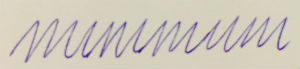

The scribbles on the right are not just doodles, a badly drawn rough sea or an attempt by a 5-year-old to emulate grown-ups’ fascinating handwriting. A real adult has written a real word here: minimum.

The scribbles on the right are not just doodles, a badly drawn rough sea or an attempt by a 5-year-old to emulate grown-ups’ fascinating handwriting. A real adult has written a real word here: minimum.